Enhancer Journal Club: Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma

I read a neat little paper in Nature just before Christmas about enhancer hijacking, which I think is a particularly interesting topic. The original paper can be found at: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v511/n7510/full/nature13379.html

The abstract is as follows:

Medulloblastoma is a highly malignant paediatric brain tumour currently treated with a combination of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, posing a considerable burden of toxicity to the developing child. Genomics has illuminated the extensive intertumoral heterogeneity of medulloblastoma, identifying four distinct molecular subgroups. Group 3 and group 4 subgroup medulloblastomas account for most paediatric cases; yet, oncogenic drivers for these subtypes remain largely unidentified. Here we describe a series of prevalent, highly disparate genomic structural variants, restricted to groups 3 and 4, resulting in specific and mutually exclusive activation of the growth factor independent 1 family proto-oncogenes, GFI1 and GFI1B. Somatic structural variants juxtapose GFI1 or GFI1B coding sequences proximal to active enhancer elements, including super-enhancers, instigating oncogenic activity. Our results, supported by evidence from mouse models, identify GFI1 and GFI1B as prominent medulloblastoma oncogenes and implicate ‘enhancer hijacking’ as an efficient mechanism driving oncogene activation in a childhood cancer.

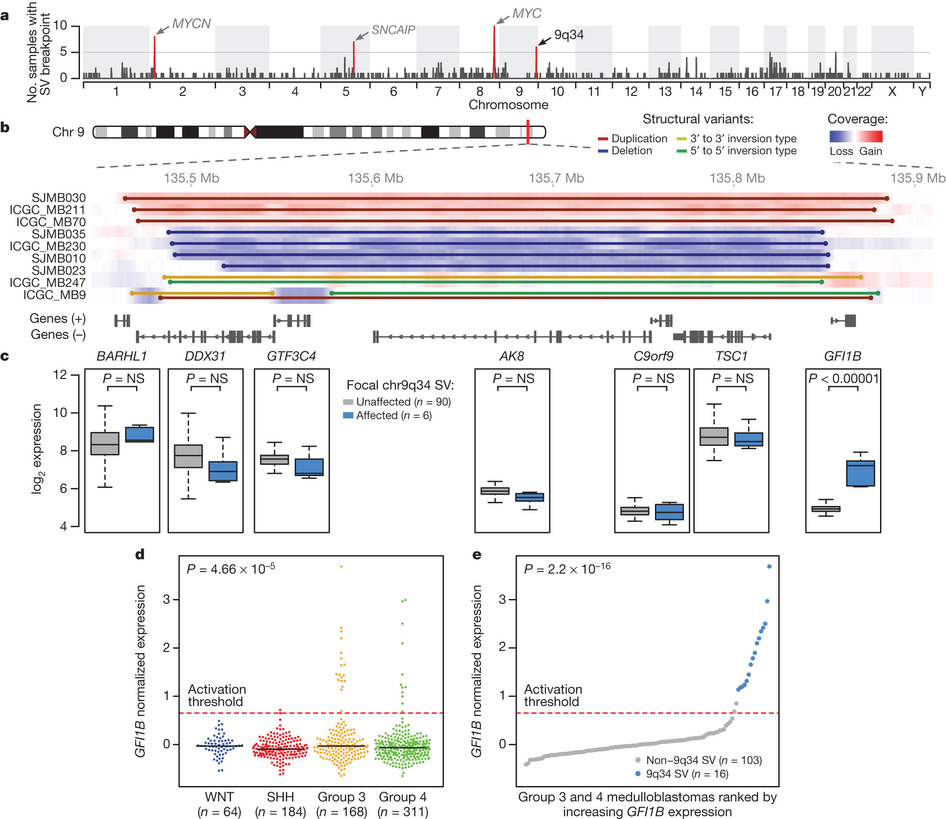

In this paper, Northcott, Lee, Zichner and colleagues explore potential molecular drivers of medulloblastoma. Medulloblastomas are though to be divisible into four main subgroups. Groups 1 and 2 generally involve upregulation of sonic hedgehog or wingless pathways, whereas groups 3 and 4 have no known cause. By sequencing tumour DNA from medulloblastoma patients, they are able to find a particular region near of chromosome 9 which is frequently involved in structural variation (i.e. deletion, duplications, inversions). These structural variants appear to lead to a consistent upregulation of the GFI1B gene, occurring specifically in group 3 or group 4 tumours.

Fig 1. a,b, Positions of recurrent structural variants in medulloblastoma. c, Expression of genes in affected region. d, GFI1B expression by medulloblastoma class. e, Class 3 & 4 medulloblastomas ranked by GFI1B expression. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature 511, 428–434 (2014), copyright (2014).

For me, the most interesting part of this paper is the finding that these chromosomal rearrangments frequently juxtapose the GFI1B gene with a series of enhancers in or around the DDX31 gene. The authors suggest that this might be a case of "enhancer hijacking", where an enhancer that normally activates the expression one gene changes its target and causes expression of an unrelated gene in the wrong tissue or the wrong developmental stage.

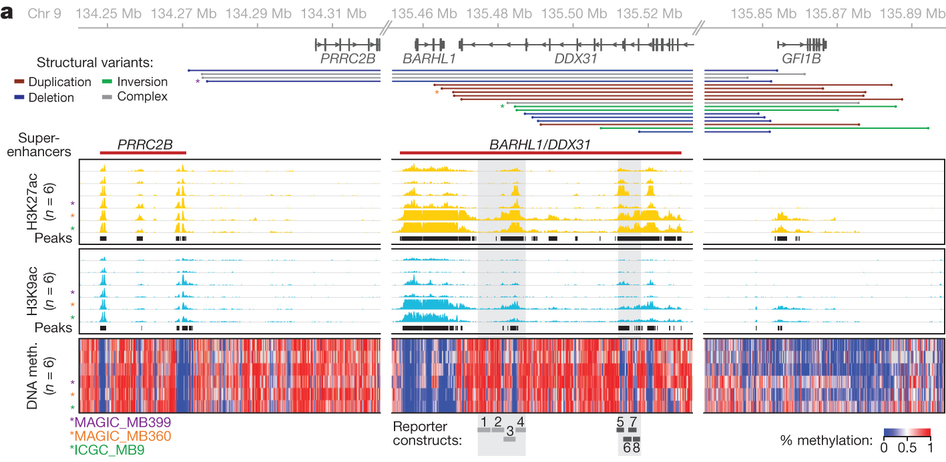

Fig 3. a, Epigenetic enhancer marks over the GFI1B/DDX31 locus. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature 511, 428–434 (2014), copyright (2014).

An interesting point to note in this figure: as the authors point out, the level of H3K27ac over the DDX31 enhancers actually seems to be higher in samples with a rearrangement in the region. Of course, this needs to be taken with a pinch of salt as you can't really compare the levels of enrichment in ChIP-seq data unless you're using some sort of fancy spike-in ChIP-seq 1

Assuming this quantitative difference is true, there may be an additional local factor which is increasing the activity of these enhancers before or after rearrangement. Interestingly, there doesn't seem to be much difference in the DNA methylation state of the enhancers in affected vs. non-affected samples. This could indicate that the enhancers are primed for further activation even in the absence of genomic rearrangements. It's possible that the increased acetylation of the enhancers could be downstream of GFI1B activation, partiularly if they are directly bound by GFI1B or one of its targets. Another alternative is that the increased activity of these enhancers is sufficient for GFI1B activation, in other words that the fully activated enhancers can activate GFI1B expression even in the absence of a genomic rearrangement. Before rearrangement, the enhancers are only separated from GFI1B by 370 kb, which is well within the range of activity seen for other enhancers.

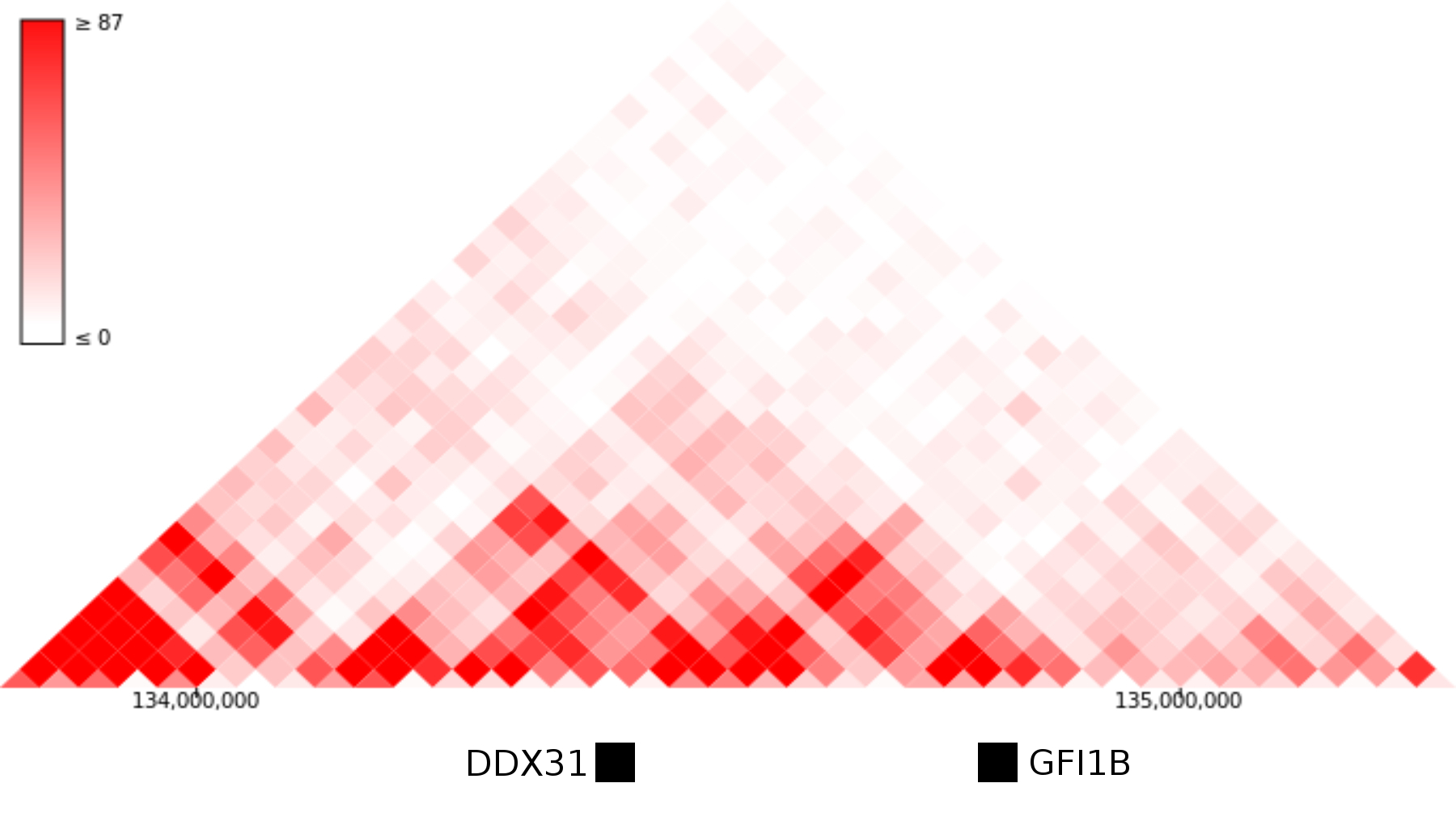

In the light of a few recent papers, perhaps the most interesting explanation is that DDX31 and GFI1B are normally separated by a topological domain boundary that gets removed or repositioned when the region is rearranged. There is some Hi-C data from an in vitro differentiation of hESCs to neural precursors, but as far as I can tell nobody has called topological domain positions from those datasets. In hESC datasets, GFI1B and DDX31 are within the same topological domain, which doesn't really support this interpretation:

Hi-C data from human ES cells suggests that GFI1B and the DDX31 enhancers may occupy the same topological domain. Image modified from the 3D genome browser - http://www.3dgenome.org

On the other hand, the whole region is syntenic between Human and Mouse, and in mouse NPCs there is a TAD boundary separating DDX31 and GFI1b. Perhaps someone could use CRISPR to delete that domain boundary in a mouse or mESC cell line and see if that causes overexpression of GFI1B.

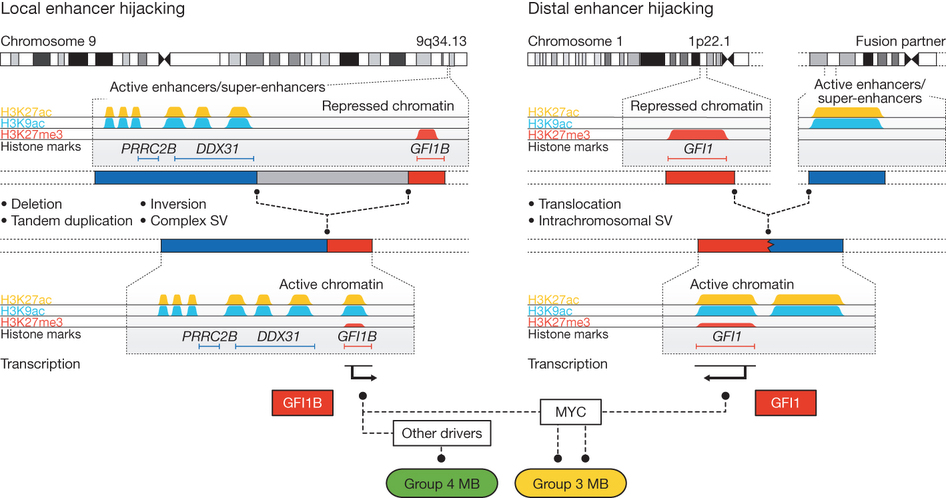

In the second half of the paper, the authors look at GFI1, which is a paralogue of GFI1B and find that GFI1 is also upregulated in a subset of medulloblastomas, and that this can be accompanied by various different chromosomal rearrangements juxtaposing GFI1 with active enhancers. One of the interesting things about these two genes is that they are both marked by H3K27me3 in unaffected samples. This means that their expression is likely to be repressed by Polycomb proteins. An interesting possibility, then, is that positioning of these genes near active enhancers is actually clearing Polycomb proteins from the GFI1/GFI1B promoters, which has been suggested as an mechanism of enhancer action in other systems 2

Fig 6 Model for enhancer hijacking in medulloblastoma. Genomic rearrangements juxtapose the GFI1B or GFI1 genes with either local or distal enhancer clusters, repressive H3K27me3 marks are lost from the respective gene promoters and GFI1/GFI1B are ectopically activated in inappropriate tissues. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature 511, 428–434 (2014), copyright (2014).

I think the idea of enhancer hijacking (or enhancer adoption, as it's also been called) is a very interesting one. The challenge remains to predict which enhancers might cause gene dysregulation when they are involved in genomic rearrangements, and crucially to determine which genes they are likely to target.

Comments !