Enhancer Journal Club: Functional annotation of native enhancers with a Cas9-histone demethylase fusion

I really enjoyed Eric Mendenhall's 2013 paper in Nature Biotechnology1, where he was able to target LSD1 histone demethylase activity to endogenous enhancers using TALE fusion proteins (read my thoughts on that paper here). So I was very interested to see a similar approach published earlier this year in Nature Methods2. In this new paper, René Maehr's group at UMass attempt to identify functional endogenous enhancers using a Cas9:LSD1 fusion protein.

Here's the abstract:

Understanding of mammalian enhancers is limited by the lack of a technology to rapidly and thoroughly test the cell type-specific function. Here, we use a nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9)-histone demethylase fusion to functionally characterize previously described and new enhancer elements for their roles in the embryonic stem cell state. Further, we distinguish the mechanism of action of dCas9-LSD1 at enhancers from previous dCas9-effectors.

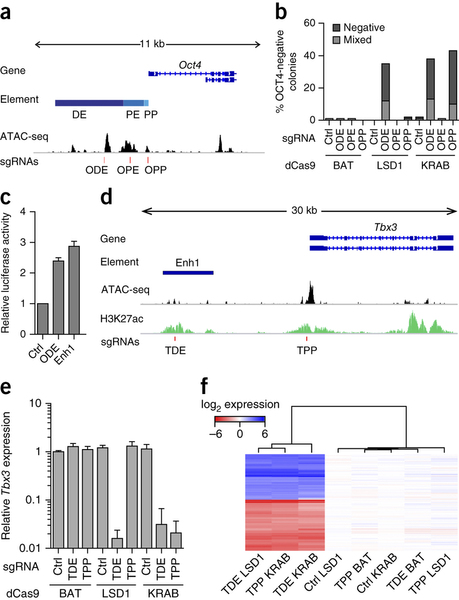

In the paper, the authors develop a Mouse ES cell line stably expressing their dCas9:LSD1, then target the LSD1 demethylase activity either to the Oct4 promoter or to the Oct4 distal enhancer by transfecting cells with guide RNAs specific to those locations. They find that targeting of LSD1 to the Oct4 promoter has no effect on Oct4 expression, whereas targeting to the Oct4 distal enhancer reduces Oct4 expression (as measured by immunofluorescence). This is in contrast to the activity of a Cas9:KRAB repressor fusion, which supresses Oct4 expression regardless of whether it is recruited to the promoter or the enhancer. They then go on on examine eight other putative enhancers of pluripotency related genes. Targeting LSD1 to these enhancers resulted in loss of pluripotency in four cases, including in an enhancer of Tbx3.

Fig 1a Genomic organization of the Oct4 locus: ODE, distal enhancer; OPE, proximal enhancer; OPP, proximal promoter; ATAC-seq signal, accessible genome; red lines indicate sgRNAs binding sites. b, Percentage of colonies that do not contain OCT4-expressing cells (negative) or that contain a mixture of OCT4-negative and OCT4-positive cells (mixed) after sgRNA delivery. c, Luciferase activity either of the ODE or of enhancer 1 (Enh1). d, Genomic organization of the Tbx3 locus including H3K27ac. e, qPCR analysis for Tbx3 expression in Nm dCas9-effector mESCs treated with sgRNAs specific to an unrelated control genomic region (Ctrl), the putative Tbx3 distal enhancer (TDE) or the Tbx3 promoter (TPP). f, Heat map of gene expression microarray data from dCas9-effector mESCs with indicated sgRNAs. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Methods 12, 401-403 (2015), copyright (2015).

In the Mendenhall et al. 2013 paper, one question I had was whether the enzymatic activity of the LSD1 is required for enhancer repression. In this paper, the authors show that simultaneously treating cells with an LSD1 inhibitor called TCP abrogates the effect of the Tbx3 sgRNA on Tbx3 expression. I still think using a Cas9 fusion to catalytically inactive LSD1 is a cleaner control, but in the end I still find the data relatively convincing. The assumption is that these LSD1 fusions (both the TALE fusions from Mendenhall et al. and the Cas9 fusion presented here) are repressing enhancers by removing H3K4me1 and H3K4me2. Although reduced H3K4 methylation and H3K27 acetylation are observed in both cases, it still remains formally possible that LSD1 is actually demethylating some other target, which is upstream (or independent of) the histone demethylation.

In the introduction, the authors hote that:

a large number of genomic regions identified by genome-wide association studies of human disease fall within enhancer regions. Thus, there is a pressing need for technologies to functionally annotate cell type-specific enhancer elements that control cellular function.

I fully agree with the authors on this point, and there is a lot of momentum within the field to develop reliable approaches which link sequence changes in enhancer regions to changes in the expression of target genes. In this light, the approach presented here is an interesting alternative, because the authors use functional assays (like looking for loss of alkaline phosphatase) rather than directly linking enhancers with target genes. I think the idea that they are getting at is that one could take a large number putative enhancers which overlap SNPs associated with e.g. Type II diabetes, and validate them by recruiting LSD1 and looking at some functional assay like glucose response. In this sense one might be able to validate that the enhancer is causally related to the disease in question without having to know exactly what gene or genes are the targets. Of course identifying the target gene is still important for developing possible therapeutic interventions.

There have been some extremely successful screening approaches developed in the past few years based on sequencing of shRNAs. For example, in Kagey et al. (2010)3 Rick Young's lab treated cells with a pool of shRNAs, used FACS to sort them for Oct4 expression and then identified shRNAs over-represented in cells with low Oct4 expression. A similar approach could be applied to the Cas9:LSD1 system, where by transfecting with a pool of sgRNAs against thousands of putative enhancers, one could systematically identify essentially all enhancers of a particular gene. I think this could be a very powerful tool for really high-throughput enhancer identification, although it would of course be limited to cell types which are amenable to both transfection and FACS sorting.

- (Mendenhall, E. M. et al., Locus-specific editing of histone modifications at endogenous enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 1133-1136 (2013).) ↩

- (Kearns N. A. et al., Functional annotation of native enhancers with a Cas9-histone demethylase fusion. Nat. Methods 12:401-403 (2015).) ↩

- (Kagey M. H. et al., Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature 467: 430-435 (2010).) ↩

Comments !